Not too long ago, I read about an exhibit at the Bullock State History Museum over at Frontier Partisans. Yes, a guy in Texas heard about an exhibit in Texas from a guy in Oregon. I’ve got to start paying better attention.

Not too long ago, I read about an exhibit at the Bullock State History Museum over at Frontier Partisans. Yes, a guy in Texas heard about an exhibit in Texas from a guy in Oregon. I’ve got to start paying better attention.

Anyway, I managed to get away over Spring Break a few weeks ago to see the exhibit. I’d like to thank Jim Cornelius for putting it on my radar.I wanted to make sure I had enough time to see everything, so I decided to stay overnight and catch the exhibit the next morning when the museum opened. I popped a Tom Russell CD in the player to set the mood and hit the road.

Not only was the exhibit great, but I saw some other great exhibits, visited some small town cemeteries, ate some great Mexican food, spent way too much time and money in second hand bookstores, and should get at least six blog posts out of the trip. (The first one on the Frank Frazetta exhibit is here.)

I’d never been to the Bullock Museum before. This trip won’t be my last. I spent half the day there, and there were some exhibits I skipped, like the food exhibit. It was making me hungry.

I’d never been to the Bullock Museum before. This trip won’t be my last. I spent half the day there, and there were some exhibits I skipped, like the food exhibit. It was making me hungry.

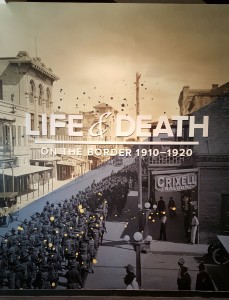

The exhibit I went to see was in the rotunda, which you can see in the photo on the left. It’s on the level with the top row windows. Much of the lighting was from the Sun shining in, so some of the pictures that follow will have some contrast to them. I apologize for the glare in some of the photos, as I was not able to get a clear shot because of the lighting.

Also, this is an extremely long post. My intention here is to allow anyone who would have liked to see the exhibit but wasn’t able to attend to experience as much of the exhibit as possible. I’ve tried to summarize the information in a coherent fashion.

When Texas won its independence from Mexico, the Mexican citizens living in Texas became first Texas citizens, then United States citizens, then citizens of the Confederacy, then US citizens again after the Civil War. These were primarily Hispanic settlers, mostly along the Rio Grande, and many of them had family in Mexico. In those days it was no big deal to travel back and forth across the border, and many did.

However, the Hispanic settlers were primarily content to farm their land, operate their stores, businesses, and ranches, and simply live their lives. These Tejanos, as they were called, had in many cases lived in the area for generations. While some were poor, a number of others were quite wealthy. Tejanos owned the majority of Cameron County’s 816,640 acres; Cameron County is at the southern tip of the state.

The mixing of early Anglos and Tejanos produced a unique culture in which families intermarried, blending the traditions of Mexico and Europe. But as Anglo land speculators opened the region for settlement, things changed for the Tejano families along the border.

The mixing of early Anglos and Tejanos produced a unique culture in which families intermarried, blending the traditions of Mexico and Europe. But as Anglo land speculators opened the region for settlement, things changed for the Tejano families along the border.

The exhibit opened with examples of high fashion, such as the wedding dress (shown left) worn by Maria de Jesus Trevino de la Garza Falcon when she wed Francisco Gonzales Cardena in 1902. Also included were examples of quilts, home altars, and Spanish primers for Anglos.

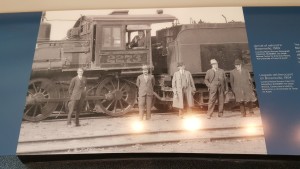

In the early 1900s railroads came to the area. With over 6,000 miles of track, Texas had the most railroad mileage in the nation by 1911; it still does. Real estate developers took advantage of the easy access to the area to bring in more Anglo settlers. Soon entire towns were founded entirely by Anglo settlers who didn’t share the culture, language, or values of the residents, Anglo and Tejano alike.

The price of land skyrocketed, jumping from $5 to $50 to $100 to $300 an acre. It didn’t help that the land records were not well kept, and just who owned a certain parcel was often in doubt. Tejanos found themselves forced from land they had owned, sometimes for generations, by fraud, theft, and intimidation as they changed from being a majority ethnic group to a minority. It was not uncommon for Tejanos to work as field hands on land they had once owned. Between 1900 and 1910, Tejanos lost more than 187,000 acres. And that was just in Cameron and Hidalgo counties.

The display case in the photo on the left shows a shovel, a hoe, and a third field tool. Land speculators often promised Anglo settlers that their fields would be worked by Mexicans. The Anglo settlers were forcing the Tejanos to become second class citizens where they had recently been the dominant group. And while there had been racial tensions before the railroads brought the influx of Anglo settlers, each year saw tensions rise between the Anglos and the Tejanos.

The display case in the photo on the left shows a shovel, a hoe, and a third field tool. Land speculators often promised Anglo settlers that their fields would be worked by Mexicans. The Anglo settlers were forcing the Tejanos to become second class citizens where they had recently been the dominant group. And while there had been racial tensions before the railroads brought the influx of Anglo settlers, each year saw tensions rise between the Anglos and the Tejanos.

In 1910, those tensions erupted.

For years the new settlers had used discriminatory tactics to disenfranchise the Tejanos citizens. Among these were poll taxes and whites-only primaries. Rather than try to assimilate into the existing culture, the new settlers viewed the Tejanos as threats to American way of life. Many called for punitive measures against the Tejanos. These measures included vigilante action.

On November 4, 1910, a Mexican citizen was pulled from his cell in Rocksprings, Texas, and burned alive at the stake. Antonio Rodriguez was accused of killing a white woman, Effie Henderson,. After being tracked down and arrested by a posse, he was pulled from his cell by a mob the next day. There were protests all along the border and in Mexico City, and American owned businesses were attacked. Mexican citizens and Tejanos demanded the vigilantes be brought to justice.

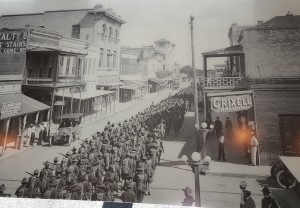

Complicating the situation on the border was the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. As the violence spread north to the Mexican border states, refugees began to spill into Texas. As these people settled in the border towns, they increased the Mexican population and strengthened local ties to Mexico. President Wilson ordered 110,000 National Guardsmen to the border to patrol on June 18, 1916.

The Revolution wasn’t simply a man’s endeavor. Many women took up arms, provided food and medical care, smuggled arms, and wrote in favor of the Revolution. When the Red Cross refused to treat Revolutionaries, Leonor Villegas de Magnon founded the White Cross. The White Cross treated wounded on all sides and was active in 25 Mexican states during the War. The photo on the right shows to White Cross workers in 1914.

The Revolution wasn’t simply a man’s endeavor. Many women took up arms, provided food and medical care, smuggled arms, and wrote in favor of the Revolution. When the Red Cross refused to treat Revolutionaries, Leonor Villegas de Magnon founded the White Cross. The White Cross treated wounded on all sides and was active in 25 Mexican states during the War. The photo on the right shows to White Cross workers in 1914.

The next set of photos will contain very little commentary from me. I’m going to include shots of the information cards provided; click to enlarge. I will caption some of the photos and/or provide brief descriptions of what the photos show for those not interested in reading the cards.

The first set of photos shows a rifle owned by Victoriano Huerta. Note the Mexican coat of arms in the closeup of the stock.

The next two sets of photos are a pair of saddles.

The first was owned by Pancho Villa.

The second saddle was owned by Venustianzo Carranza.

1915 would prove to be a significant year for border violence.

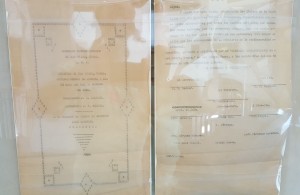

The Plan de San Diego Manifesto (shown on the right) called for an uprising of Mexicans against the “Yankee tyranny” to begin on February 20, 1915, at 2:00 a.m. In January a copy was found on Basilio Ramos, a former beer distributor from San Diego, Texas, in Duval County. Mexican and African Americans, American Indians, and Japanese citizens were called upon to rise up and execute Anglo males above the age of 16 as well as “traitors to the race.” The Manifesto called for Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California to declare their independence. Ramos was jailed on charges of attempting to levy war; his bond was set a $5,000. No invasion took place, but as news of the Manifesto spread, unrest grew.

The Plan de San Diego Manifesto (shown on the right) called for an uprising of Mexicans against the “Yankee tyranny” to begin on February 20, 1915, at 2:00 a.m. In January a copy was found on Basilio Ramos, a former beer distributor from San Diego, Texas, in Duval County. Mexican and African Americans, American Indians, and Japanese citizens were called upon to rise up and execute Anglo males above the age of 16 as well as “traitors to the race.” The Manifesto called for Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California to declare their independence. Ramos was jailed on charges of attempting to levy war; his bond was set a $5,000. No invasion took place, but as news of the Manifesto spread, unrest grew.

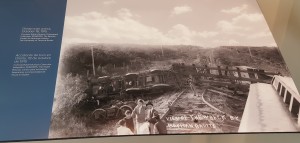

In 1915 ethnic Mexicans began raiding at the southern tip of Texas, rustling cattle, robbing Anglo businesses, killing farmers, and burning railroad bridges. Known as los sediciosos, their actions were embraced by some Tejanos and repudiated by others. They believed their actions were a fight for Mexican rights against the brutal and prejudiced United States. The government, both state and national, sent Texas Rangers and federal soldiers to try and restore the peace. It would not be the Rangers’ finest moments.

In 1915 ethnic Mexicans began raiding at the southern tip of Texas, rustling cattle, robbing Anglo businesses, killing farmers, and burning railroad bridges. Known as los sediciosos, their actions were embraced by some Tejanos and repudiated by others. They believed their actions were a fight for Mexican rights against the brutal and prejudiced United States. The government, both state and national, sent Texas Rangers and federal soldiers to try and restore the peace. It would not be the Rangers’ finest moments.

The King Ranch is one of the largest in the state of Texas. On the morning of August 8, 1915, los sediciosos attacked the Noriegas Division of the King Ranch, setting off a wave of violence in the Rio Grande Valley that lasted for eight weeks and involved raids on post offices, railroad bridges, and even the US Cavalry. Many Anglo ranchers and business men had moved their families out of the area by the end of September for protection.

The King Ranch is one of the largest in the state of Texas. On the morning of August 8, 1915, los sediciosos attacked the Noriegas Division of the King Ranch, setting off a wave of violence in the Rio Grande Valley that lasted for eight weeks and involved raids on post offices, railroad bridges, and even the US Cavalry. Many Anglo ranchers and business men had moved their families out of the area by the end of September for protection.

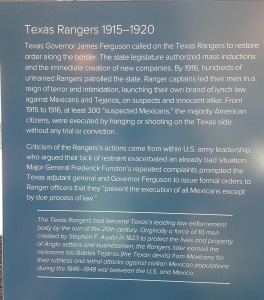

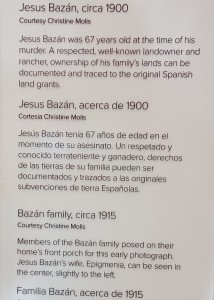

The Texas Rangers didn’t exactly do a lot to suppress the violence, and often added to it. (See image on left for more detail.) On September 24, 1915, James McAllen’s ranch in western Hidalgo county was attacked by raiders. The raid wasn’t exactly a success. Two of the raiders were killed and several others were injured. The raiders retreated to a nearby ranch owned by Tejanos. This was pretty much the kiss of death for the Tejanos. If they denied the raiders aid, they would have been killed, if not by the raiders themselves, by others. It wouldn’t have been the first time Tejanos were killed by los seciciosos or other militant Hispanic groups. On the other hand, the Texas Rangers considered any Tejanos who gave aid to raiders to be complicit in the raids. A few days after raid, Texas Rangers observed Jesus Bazan and Antonio Longoria riding towards the ranch where the raiders had taken refuge. Bazan and Longoria were upstanding members of the community who had not take part in any of the raids (see the information in the photos below). Nevertheless, the Rangers shot the men in the back. Their bodies were discovered four days later by a local ranch hand who buried them. Their graves are still visible just off FM 1017 in Hidalgo County.

The Texas Rangers didn’t exactly do a lot to suppress the violence, and often added to it. (See image on left for more detail.) On September 24, 1915, James McAllen’s ranch in western Hidalgo county was attacked by raiders. The raid wasn’t exactly a success. Two of the raiders were killed and several others were injured. The raiders retreated to a nearby ranch owned by Tejanos. This was pretty much the kiss of death for the Tejanos. If they denied the raiders aid, they would have been killed, if not by the raiders themselves, by others. It wouldn’t have been the first time Tejanos were killed by los seciciosos or other militant Hispanic groups. On the other hand, the Texas Rangers considered any Tejanos who gave aid to raiders to be complicit in the raids. A few days after raid, Texas Rangers observed Jesus Bazan and Antonio Longoria riding towards the ranch where the raiders had taken refuge. Bazan and Longoria were upstanding members of the community who had not take part in any of the raids (see the information in the photos below). Nevertheless, the Rangers shot the men in the back. Their bodies were discovered four days later by a local ranch hand who buried them. Their graves are still visible just off FM 1017 in Hidalgo County.

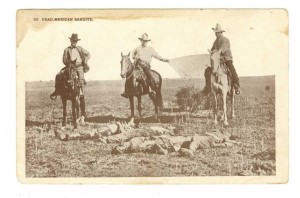

It was a common practice at this time for the soldiers to send picture postcards of themselves home to friends and family. One example is the image on the right entitled “Dead Mexican Bandits”. I got this version online. All my shots had too much glare. Google “Dead Mexican Bandits” and you’ll get a number of similar images. This photo was taken in 1915. After a raid on the Norias Ranch, four Tejanos were killed and left for dead. Three of them were identified as Juan Tobar, Abraham Selina, and Eusebio Hernandez. the morning after their bodies were found Captain William Hanson, Captain James Monroe Fox, and a third Texas Ranger posed with their lassos around the bodies. Once the postcard was distributed, the Tejano community was outraged at how their dead were treated. Can’t say i blame them one bit.

It was a common practice at this time for the soldiers to send picture postcards of themselves home to friends and family. One example is the image on the right entitled “Dead Mexican Bandits”. I got this version online. All my shots had too much glare. Google “Dead Mexican Bandits” and you’ll get a number of similar images. This photo was taken in 1915. After a raid on the Norias Ranch, four Tejanos were killed and left for dead. Three of them were identified as Juan Tobar, Abraham Selina, and Eusebio Hernandez. the morning after their bodies were found Captain William Hanson, Captain James Monroe Fox, and a third Texas Ranger posed with their lassos around the bodies. Once the postcard was distributed, the Tejano community was outraged at how their dead were treated. Can’t say i blame them one bit.

Not all of the postcards were of such a grisly nature. The three postcards on the left show soldiers in a variety of activities.

Not all of the postcards were of such a grisly nature. The three postcards on the left show soldiers in a variety of activities.

Some Anglo newspapers called for the eradication of the Tejano and Mexican populations. The number of people who were tortured and/or killed in 1915 reached into the hundreds. Corpses were left to rot in the sun because people were afraid to be seen burying the bodies. Headless corpses floated down the Rio Grande. Brownsville attorney and local historian personally identified 102 victims. I have no idea how many he wasn’t able to identify or how many dead were identified by other investigators. For the next decades corpses with execution style bullet holes in their skulls were found in brush.

When World War I broke out, many Hispanic citizens supported the United States and entered the armed forces where they served with distinction. Still they were mistrusted along the Border, especially after the release of the Zimmerman Telegram, in which the German government attempted to entice Venustiano Carranza’s government to enter the war. He wasn’t interested, but the release of the telegram convinced many that Tejanos were disloyal.

When World War I broke out, many Hispanic citizens supported the United States and entered the armed forces where they served with distinction. Still they were mistrusted along the Border, especially after the release of the Zimmerman Telegram, in which the German government attempted to entice Venustiano Carranza’s government to enter the war. He wasn’t interested, but the release of the telegram convinced many that Tejanos were disloyal.

Woodrow Wilson went to great lengths to prosecute anyone who was deemed disloyal. Governor Hobby appointed three Loyalty Rangers in every county to monitor disloyal activity and speech. The fact that these efforts by the government, both state and national, were unconstitutional and violated the rights of both the Anglo and Tejano populations was conveniently overlooked.

Reports of raiders attacking the L. C. Brite ranch in west Texas began to circulate on December 25, 1917. Three people were murdered. The nearby town of Porvenir (170 miles SE of El Paso), which was almost entirely Tejano, was blamed. Company B of the Texas Rangers believed the raiders were being hidden in the village. On January 28, 1918, with assistance from the 8th Cavalry, the Rangers made an early morning raid. The Tejano and Mexican population were held at gunpoint while the Rangers searched their homes looking for stolen property and probably anything else incriminating they could find. (“Warrants? We don’t need no stinkin’ warrants!”) As you might imagine, they didn’t find anything. Still, they wanted to let the Tejano population know that aiding and abetting raiders would be met with swift punishment. So they executed 15 men. Fearing for their lives, 140 people fled to Mexico. Among them were the brothers Juan and Narcisco Flores, whose father Longino was one of the men shot and killed in the massacre. (See the photos below for more information on the Flores brothers.) Governor Hobby disbanded Company B five months later, but none of the perpetrators of the Porvenir Massacre were ever indicted for their crimes.

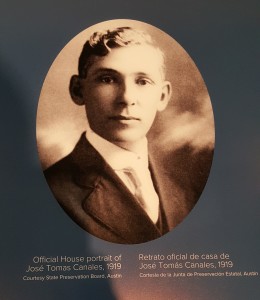

In 1919, there was only one member of the Texas Legislature of Hispanic descent, Jose Tomas Canales of Brownsville. But sometimes one man is enough. In spite of threats on his life, Canales introduced a bill to change the makeup of the Texas Rangers. Hes also requested a joint hearing of both Houses of the Legislature to investigate the Rangers. For three weeks the testimony of over 90 witnesses was heard in a high profile series of hearings. The panel found the Rangers “guilty of, and are responsible for, the gross violation of the civil and criminal laws of the state.”

Although Canales’ original bill was altered, a version was passed. The appointments of most Special Rangers were cancelled, several companies were disbanded, and all Rangers, current and future, underwent a more rigorous screening process.

Although Canales’ original bill was altered, a version was passed. The appointments of most Special Rangers were cancelled, several companies were disbanded, and all Rangers, current and future, underwent a more rigorous screening process.

The violence subsided, but racial problems persisted. Juan Crow laws, based on the Jim Crow laws of the South, denied many Hispanic citizens their rights. The Ku Klux Klan was active in the state, and they marched in the Rio Grande Valley. Poll taxes and other methods of disenfranchisement were common. Veterans were denied burial in cemeteries solely on the basis of their race. (This sort of thing is still going on. There was a story on the news a few weeks ago about the caretaker of a cemetery somewhere in Texas, I didn’t catch where, who is denying a widow the right to bury her husband because he was Hispanic.)

However, Hispanic citizens began to organize and work for their civil rights. The exhibit ended with a few brief descriptions of some of these efforts.

Again I would like to thank Jim Cornelius for posting about this exhibit. It was a great thing to visit, as was the rest of the museum. There wasn’t a particular book devoted to the exhibit, but I did pick up copies of two that were related. The first is Bosque Bonito, a memoir by a Cavalryman who was stationed in the Big Bend during this period. The other is a history of the Plan de San Diego and the events that followed, Revolution in Texas. (Jim, they only had one copy of this one, and it was priced over the limit you gave me.) I’m looking forward to reading them. I also got some other books that I’ll be using as references for future posts.

This is a great post. Thanks for the vicarious thrills.

You’re welcome. Glad you liked it.

Amazing write up. Thank you.

Thanks. I wanted this one to be a top-notch job, not something I just dashed off.

Outstanding! Thanks for getting the guy from Oregon close to the exhibit in Texas. Really appreciate the detailed post.

Jim Cornelius

http://www.frontierpartisans.com

You’re welcome, and I’m glad you liked it. I knew there would be people, yourself included, who would have been there if they could, so I wanted to share as much of the exhibit as I could.

Great piece!

I love the history and the way we can see how we’ve changed (or not).

How’d they get Pancho Villas saddle?

And those postcards! Awesome!

Wild West justice indeed.

Thank you. There’s a lot of good history in this exhibit, much that would lend itself to historical fantasy. I have no idea how they got either of the saddles. The fine print on the info cards say they’re on loan from the same place.

If this doesn’t spur me to read more about Pershing in Mexico this year, I don’t know what will. Dynamite piece, Keith

Thank you.

Gloria, I read the whole thing. Want to go see other exhibits at the museum. This was fascinating. Gracias.