“The Lion and the Unicorn”

“The Lion and the Unicorn”

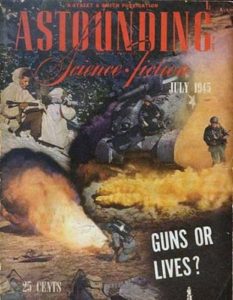

Originally published in Astounding Science Fiction, July 1945

This is the third installment of the Baldy series, written by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore under their joint pen name of Lewis Padgett. The reviews of the preceding two stories can be found here and here.

Spoilers to follow.

“The Lion and the Unicorn” opens only a few decades after “Three Blind Mice”. Barton, the protagonist of the previous tale, is still alive. He’s in his sixties, and while a key player, he’s not the central figure in this story. Barton managed to kill the Baldies who had developed the alternate wavelength, but there are others. It turns out the ability to send and receive telepathic messages on this alternate wavelength is a new mutation on the Baldy mutation. And all the Baldies who have it are paranoid.

The conspiracy has grown. When the story opens, Darryl McNey is waiting for Sergei Callahan and Barton. Callahan is a leader of the paranoid mutants. McNey hopes to convince him that his plans to wipe out normal humans is wrong and doomed to failure. He doesn’t succeed. Callahan thinks that the Baldy mutation produced supermen, and that they have the right to wipe out and/or rule over normal humans. He and his cohorts plan to instigate another war, and rise from the ashes to rule.

Considering that this story was written during the closing days of WWII, it’s not surprising that the Kuttners are dealing with themes of supermen who want to rule over those they see as inferior races. Now I wonder what could have inspired them to adopt this theme? The whole conversation between McNey, Callahan, and Barton sounds an awful lot like a discussion of the Final Solution. It also sounds like Communist infiltration, which was becoming a concern at the time. Callahan talks of propaganda and misinformation, of a centralized authority, of secret cells working together yet independent of each other to sow discord and mistrust, with the ultimate goal of goading normal humans into starting another war, one that will leave them crippled and vulnerable.

When humanity’s lowered to a more vulnerable status, we can centralize and step in. There aren’t many truly creative technological brains, you know. We’re destroying those – carefully. And we can do it, because we can centralize mentally, through the Power, without being vulnerable physically…You can’t kill us all. If you knifed me now, it wouldn’t matter. I happen to be a co-ordinator, but I’m not the only one. You can find some of Us, sure, but you can’t find Us all, and you can’t break Our code. That’s where you’re failing, and why you’ll always fail.

The meeting ends with each side more resolved to defeat the other. After accusing the two men of wanting to water-down the genetic strain that makes a Baldy by intermarrying with normal humans, Callahan leaves. Barton goes to find a Baldy who is living with a group of Hedgehounds.

The Hedgehounds are semi-feral humans who refuse to live inside cities and roam the countryside. Kuttner portrays them as being like a modern day version of American Indians, including the use of the word “squaw”. They make the occasional raid into a town, but as a general rule are not much more than a nuisance and are left alone most of the time. If they become too much of a problem, they’re hunted down. But if a Baldy is with them, well, that could spell trouble for all the Baldies.

The particular Baldy in question is Lincoln Cody, who goes by the name of Linc. He doesn’t know he’s a mutant or that he’s a telepath. He just knows that he can sometimes tell what people are going to do or say in advance. In short, he’s an untrained telepath. He’s got a wife, Cassie, but he has never really felt like he belongs with his tribe. Trouble is brewing between him and the leader when Barton makes contact with him one night.

At first Linc is hesitant and a little suspicious (who could blame him?), but in the end he goes with Barton back to civilization without saying goodbye. Linc finds the acceptance and emotional intimacy that has eluded him all his life. He works hard to fit in, with no plans to return to his old way of life. He begins to fall in love with McNey’s daughter Alexa, who is his tutor. Barton and McNey even have a conversation about the expectations of the two marrying.

Those expectations are shattered when one afternoon Linc comes upon Alexa sunbathing, “her flimsy playsuit unzipped to let the slight breeze cool her.” That’s not what gets Linc’s attention, though. It’s Alexa’s bald head; she’s removed her wig. Linc grew up in a culture in which hair was not only a sign of beauty, but it helped in survival by helping keep your head warm in winter. Although he knew Alexa was as bald as a billiard ball, this is the first time he’s seen her without her wig. A wave of revulsion sweeps over him, one he tries to damp out, but she picks up on it. Acknowledging to each other that Linc’s deep-seated prejudices make marriage impossible because Alexa knows how he feels about her appearance, they agree that marriage won’t be an option. They verbally, not telepathically, say goodbye.

Not long after this, Linc goes in search of McNey only to discover the man is wounded and will bleed to death if he doesn’t get medical help. Sergei Callahan has stabbed him and is waiting in hiding for Linc. Linc is untrained, but his telepathic ability is enough to let him know Callahan is waiting behind a heavy steel door. Before Callahan is able to get out from behind the door, Linc manages to push the door against the wall and crush Callahan.

McNey gets the medical help he needs and recovers. He’s been working on an equation that will let him come up with a screening device that will protect his thoughts from telepathic eavesdropping. He’s held off on solving the equation because he doesn’t want one of the paranoids reading his mind. Late one night, after his wife has gone to bed, he solves the equation, builds a cap that will protect the Baldy wearing it from telepathic eavesdropping, destroys his derivation of the equation, and leaves instructions on how to make more of the caps. Then he takes his own life so no one can read his mind.

Linc, meanwhile, has returned to his tribe. Cassie is thrilled to see him, and she introduces Linc to someone who arrived while he was gone. His son. His bald son. It seems the mutation breeds true.

I can see the hand of John W. Campbell, Jr., in this tale. Campbell talked through story ideas with many of his stable, often pitching the same idea to multiple authors at once just to see what the result would be. The logic in this story is pretty rigorous, although I’m not so sure most women would be as casual about being abandoned as Cassie is. The implications of the secondary mutation, with the restricted telepathic frequency only available to paranoid mutants, is further developed.

There is still quite a bit of exposition in this story, but the addition of the Hedgehounds provides a nice contrast to the long-winded Baldies. Linc’s presence adds a level of action that the previous stories were missing. Still, upon rereading these tales, I can understand why I’ve not reread the Baldy stories since I first encountered them, with the exception of “The Piper’s Son”. They’re pretty grim, missing Kuttner’s frequent comic relief, and have a bit more discussion (for lack of a better word) than most of what I’ve read of Kuttner’s work. Note that discussion and dialogue aren’t quite the same thing, although they are closely related. Kuttner’s stories, both individually and in collaboration with Moore, tend to have at their center a kernel of an idea that he develops throughout the story. The ideas here are bleak, not something rare in Kuttner’s work, but they seem to have a bit more of Campbell than you normally see in the stories Kuttner and Moore placed in Astounding.

I like the Baldy stories, but they aren’t my favorites. Too much of what happens is inside people’s heads. The bleak outlook isn’t really a problem. Some of my favorite Kuttner stories have dark endings. Stories such as “Mimsy Were the Borogoves”, “When the Bough Breaks”, “We Kill People”, and “Happy Ending” (which doesn’t have a happy ending). I doubt we’ll ever know just how much of these stories is Campbell unless someone publishes correspondence in which they discuss the series.

There are two more stories in this series, and we’ll look at both of them.