Devil’s Garden

Devil’s Garden

Ace Atkins

Putnam

paper $16.00

ebook $11.99

At one point in The Lost Detective, Nathan Ward mentioned that Hammett had worked for a time on the Arbuckle case. And that reminded me that Ace Atkins had written a novel about Hammett’s work on the case which I had been wanting to read. So I did.

For those who may not be aware of the Arbuckle case, and I’m assuming that’s going to be many of you because Arbuckle is pretty much forgotten these days, it changed Hollywood and the studio system forever.

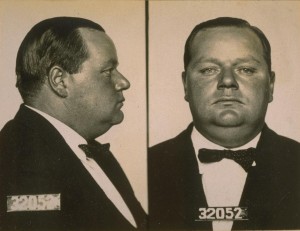

The basics of the case are these. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was a silent film comedian in the nineteen teens. He was at least as big as Charlie Chaplin (whose career he had aided while they were both at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios), discovered Bob Hope, and helped a young man named Buster Keaton transition from vaudeville to film.

Over the Labor Day weekend in 1921, Arbuckle drove his custom made Pierce Arrow (it had a bar and a toilet in it) from Los Angeles to San Francisco where he and two friends rented a suite of rooms at the Saint Francis Hotel. A full scale party ensued with plenty of booze despite Prohibition. During the festivities, an actress named Virginia Rappe, accompanied by a woman named Maude Delmont and a male friend, went to Arbuckle’s party, although none had been invited by Arbuckle.

During the festivities Virginia went into one of the bedrooms. When Arbuckle came in to wash up before going for a drive with a friend, he found her vomiting in the bathroom. He helped her to the bed. A little later, Virigina went into hysterics, complained about abdominal pain, and began ripping off her clothes. A hotel manager was called, and Virginia was moved to another room. Arbuckle returned to Los Angeles; Virginia Rappe was eventually moved from the Saint Francis to a sanitarium where she died that Friday. An illegal autopsy (performed without the coroner’s approval) revealed the cause of death to be peritonitis from a ruptured bladder.

Maude Delmont accused Arbuckle of raping Virginia Rappe. The story grew wilder with each retelling, morphing into he raped her with a piece of ice to he raped her with a bottle. Arbuckle was arrested and vilified in the press, particularly in papers owned by William Randolph Hearst. After three trials (the first two ending in hung juries), Arbuckle was acquited. The jury members all signed a letter of apology to him, something that was unparalleled. Maude Delmont was the prosecution’s star witness, yet she was never called to testify at any of the trials.

Arbuckle’s career, however, was over. He lost his fortune. His films not only were banned, but many of them were destroyed. (A complete filmography is almost impossible because Arbuckle was prolific and much of his work has been lost.) And he found himself blacklisted by Will H. Hays, who had assumed the position of President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. He had just returned to making films when he died in 1932.

Devil’s Garden is just as much about Hammett as it is about Arbuckle. Hammett did work on the case, but how much work he did is unclear. He probably wasn’t as involved as Atkins portrays. He does incorporate a number of biographical tidbits about Hammett into his narrative.

Atkins did his research well, although he does appear to take a bit of dramatic license with some of the details and timeline. For example, it appears he has Hammett working as a Pinkerton a bit longer than he actually did. Also, according to all accounts I’ve read by those who knew him, Arbuckle was not a ladies man, nor did he step out on his wife. (They were divorced by the time of the party.) Atkins portrays Arbuckle as more of a philanderer.

Still, these are minor quibbles. Atkins takes two historical figures whose paths crossed and manages to weave a cohesive story out of the facts that is entertaining and compelling. And Arbuckle and Hammett aren’t the only historical figures with shady pasts who show up. Atkins gives us a view into another world. After all, (to steal a quote) the past is foreign country. They do things differently there.

While I might have some minor quibbles about the details, Ace Atkins has produced a dark novel than ranks alongside some of the best period noir I’ve read.

Plenty of noir fodder in early Hollywood. Arbuckle, Thelma Todd’s death, the failed actress that threw herself off the HollywoodLand sign.

Not to mention the murder of William Desmond Taylor. Then there was a director named Thomas Ince who died on Hearst’s yacht. The supposed cause of death was heart failure, but rumors quickly spread that Hearst had shot him. The story was that Hearst caught Chaplin in a compromising situation with his mistress, Chaplin fled with Hearst in pursuit, and Hearst mistakenly shot Ince in the dark, believing he was Chaplin.

That needs to be written.

Agreed. I don’t have the time to do the research to make it a historical piece. Maybe if I change the names…

Since writing this post, I’ve read a more recent book, Room 1219 by Greg Merritt. He examines the evidence and the testimony of some witnesses who testified at some of the pretrial hearings but were never called on at the trial. Merritt thinks it was because their testimony supported neither the prosecution nor the defense narratives. His explanation is pretty plausible (and more detailed than I’m going into here).

Oh, and apparently Arbuckle didn’t have a toilet in his car, which still exists. See pictures here:http://www.autocollections.com/index.cfm?id=1239&action=details&tab=inventory&cartable=&sortorder=car,year&sr=53